Generated by Nano Banana Pro with prompt “A modernist square staircase descending in right angles, each corner turning inward to form a smaller square of stairs, repeating infinitely toward the center, viewed from directly above”

How AI Coding Agents Hid a Timebomb in Our App

When a deleted comment led to deleted code and React’s Activity component masked the infinite recursion

Crash reports started trickling in. Users would be working as normal in the app until, without warning, the browser locked up. Behind the scenes, an infinite React component tree was quietly growing in memory, and React 19’s <Activity> was keeping it alive long enough to hide the problem. The culprit? An AI coding agent and a deleted comment.

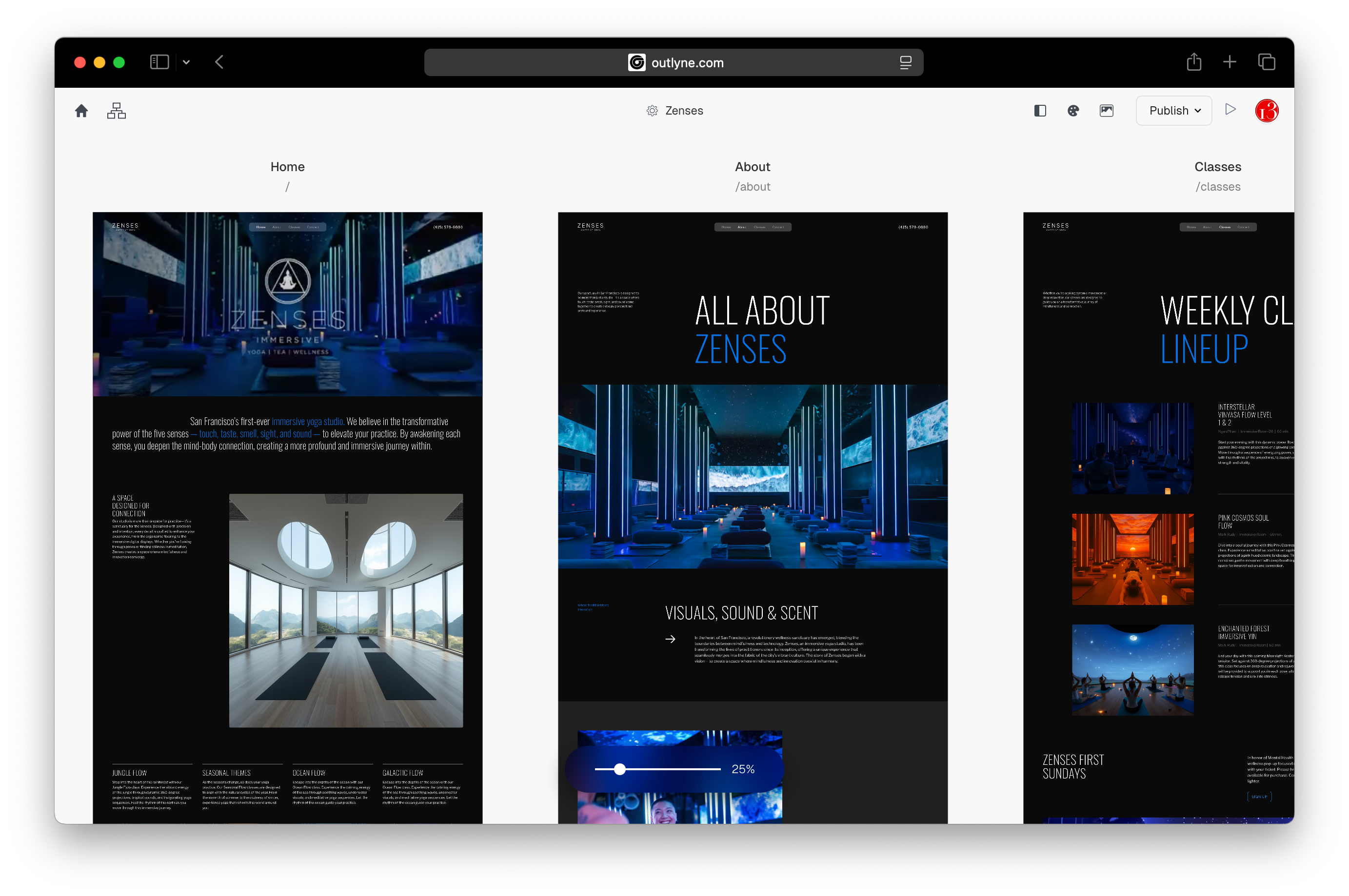

I’ve been building Outlyne, an AI-powered website builder, with my co-founder for the last year and a half. The primary UI is a Figma-like canvas with the pages of your website lined up horizontally:

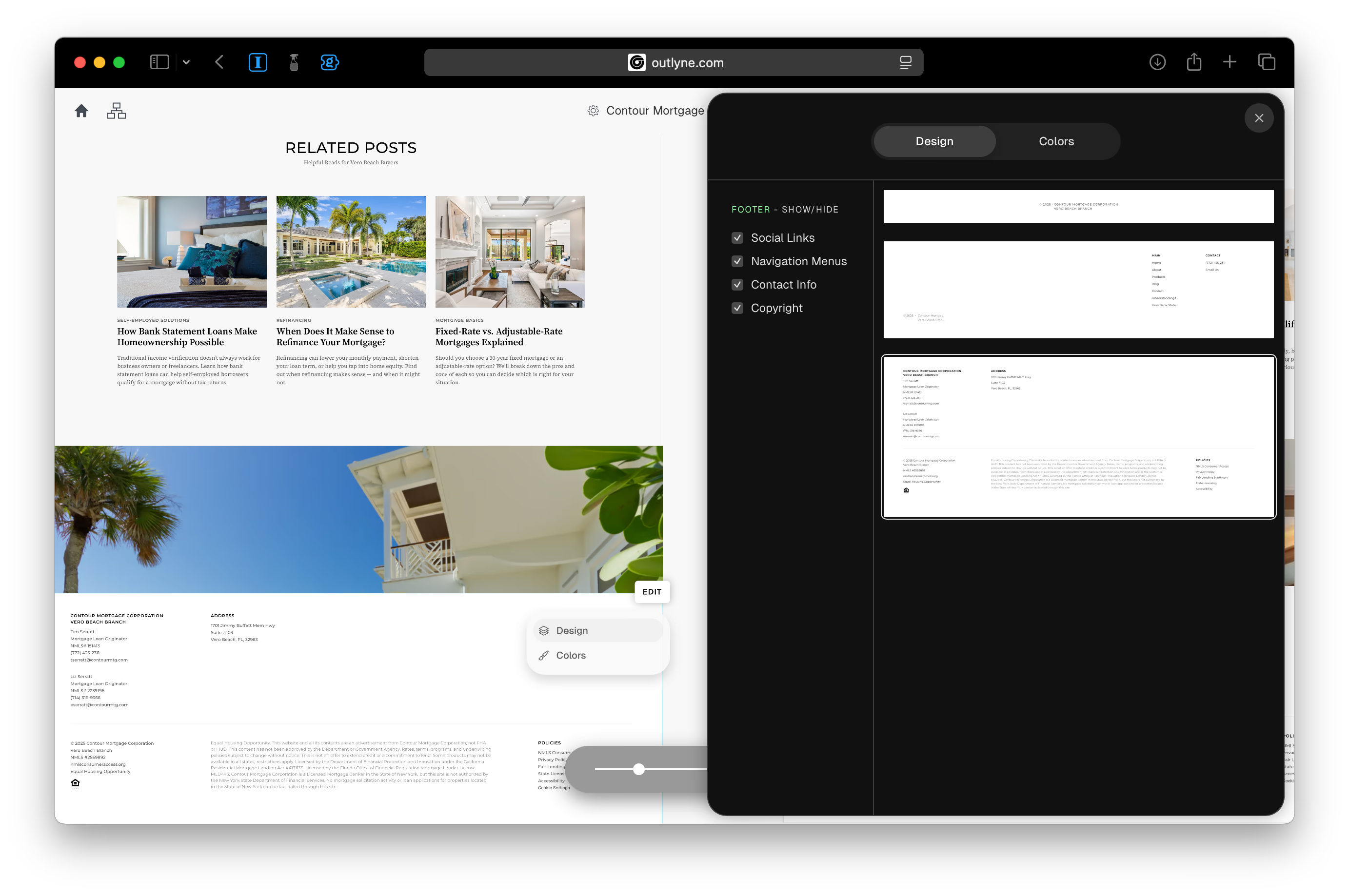

Each page has a header and footer, and each header and footer render an HTML popover that opens as a sidebar on the right so that users can choose between header and footer variants and decide what content to include:

The variants are rendered as scaled-down versions of the actual header and footer components, so the page’s header and footer each render a UI that itself renders more headers and footers with different props. That’s inherently recursive, which is fine as long as the recursion bottoms out. But if a preview ever renders the editor UI, which then renders previews again, the recursion never stops, and you end up in an infinite render loop.

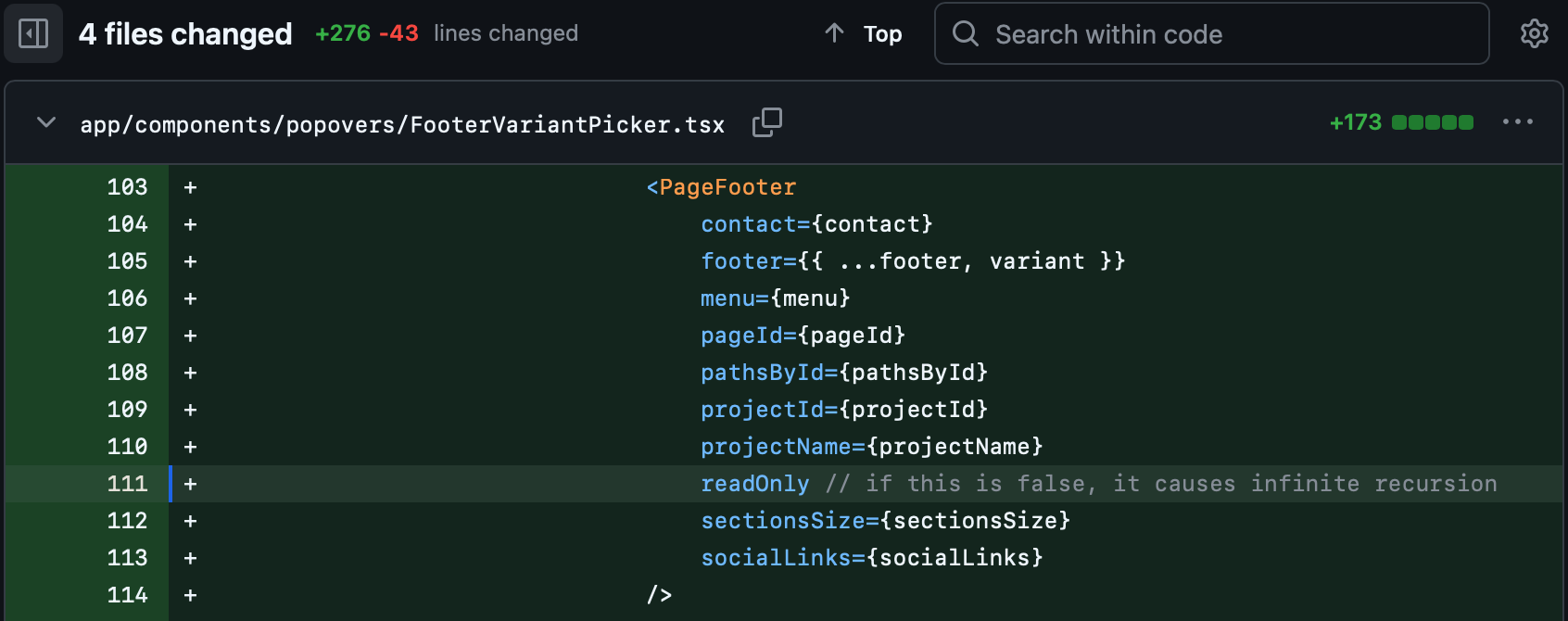

Outlyne’s architecture made the solution straightforward. Webpage components only include the content and functionality needed for the published page. The editing UI is completely separate, imported via React.lazy and Suspense and only rendered when the page is editable. Published pages get zero editing UI in their JS bundle. So when I implemented the header and footer variant previews, I set readOnly={true} for the previews. They render only the content, no editing UI. Perfect! Easy-peasy. But also important, so let’s add a comment warning that “if this is false, it causes infinite recursion”:

AI Coding Agents

We use AI coding agents. We’d be crazy not to. They’ve been an enormous productivity multiplier for us, especially in routine refactors and UI cleanup work, and it’s incredibly tempting (and productive) to just trust the changes they make.

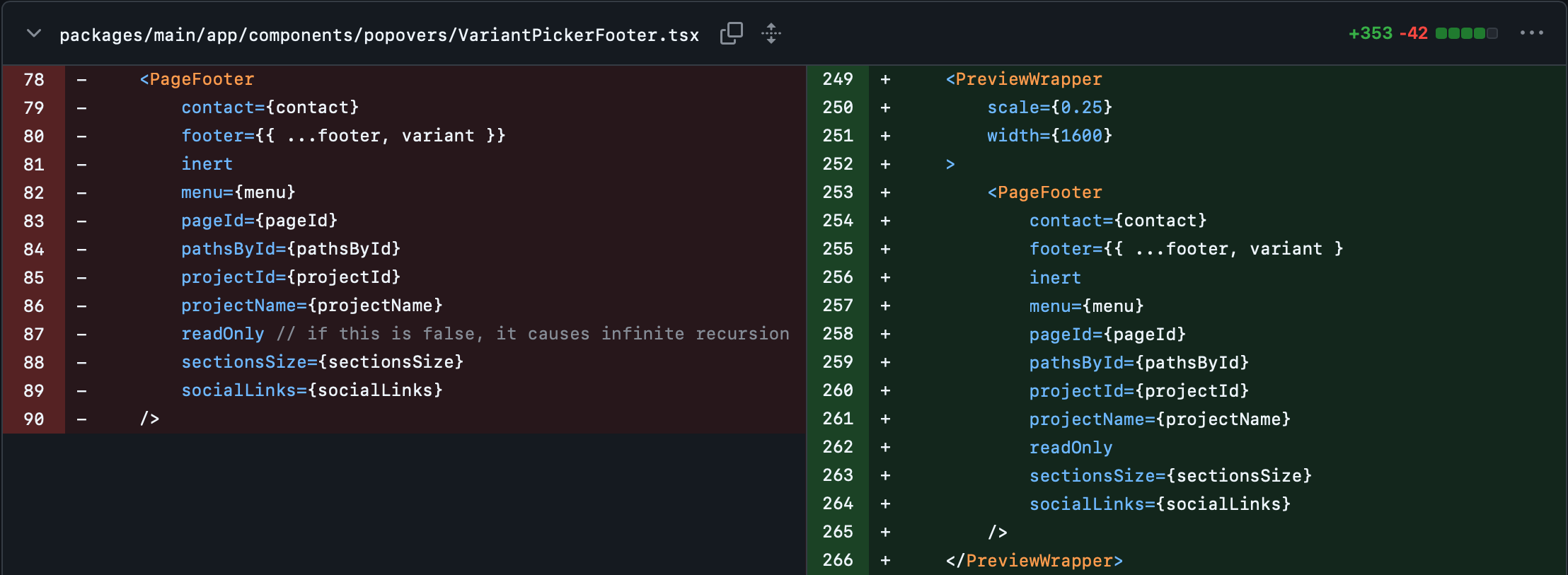

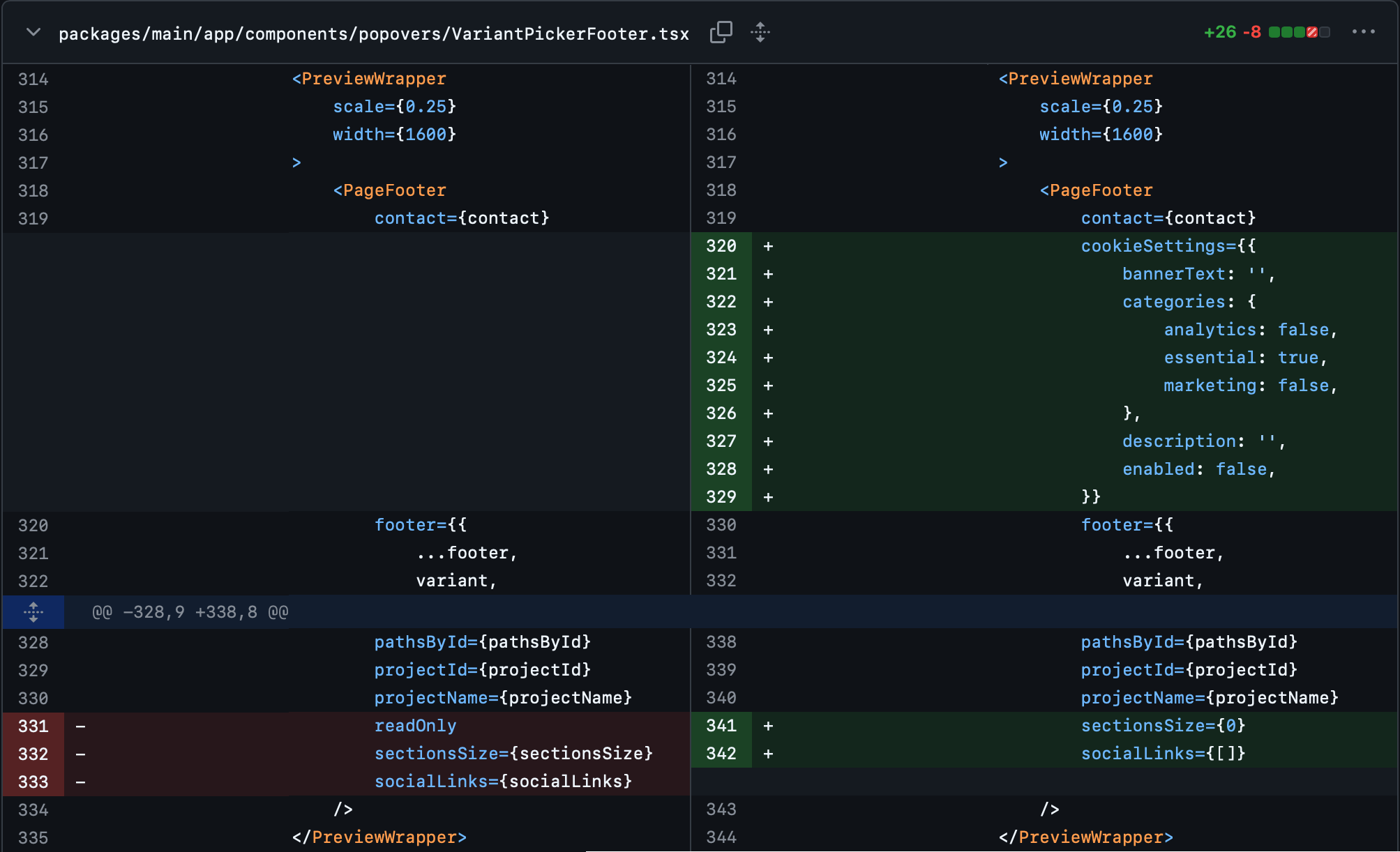

A couple of months ago, we redesigned and improved the UI for editing headers and footers. We created a tabbed interface to hold the variant and color options and wrapped the previews in a new PreviewWrapper component. And the AI removed my comment, I guess as cleanup? Maybe because “infinite recursion” sounds like no big deal? Well anyways, 353 changed lines, LGTM, merge it.

Once that comment disappeared, the AI no longer had any signal that readOnly was a structural safety constraint rather than just another prop.

Sure enough, four weeks later, we added a cookie consent feature for websites that have cookies and want to be GDPR compliant, which meant updating the footer to pass a new cookieSettings prop. While in there, we optimized the previews to use static empty values for some of the props that don’t matter in a preview. Oh, and the LLM decided to remove that readOnly prop. With no comment providing context, there was nothing to signal this wasn’t safe to touch.

The App Kept Working

We tested the changes, things looked good, we deployed. Everything seemed fine. Then reports started coming in: browsers were freezing and crashing.

When I opened the app to investigate, I expected an immediate crash. Instead, it loaded normally. I could navigate around, edit content, everything worked as usual. It took several minutes before my browser finally gave up and crashed.

This shouldn’t have been possible. We had popovers rendering infinite trees of components, each footer preview rendering another footer, which rendered another preview, which rendered another footer, and so on. Normally, React would try to render that entire tree immediately and the app would crash on load. But React 19.2’s new <Activity> component changes how hidden UI is rendered. In our case, it didn’t just hide the UI—it hid the bug.

We wrap our editing popovers in <Activity mode={popoverState === 'closed' ? 'hidden' : 'visible'}>, so when the popover is closed on initial load, the entire editor UI is rendered in hidden, low-priority mode. React still renders it, but gradually, spread out over time, and without effects or DOM commits. That meant the infinite tree was quietly expanding in memory in the background while the visible UI stayed perfectly responsive. The bug was there immediately, but <Activity> shielded the user from seeing it until the browser finally ran out of memory minutes later.

<Activity>’s extremely efficient implementation of component pre-rendering had masked the timebomb we’d introduced into our codebase.

Finding the Culprit

The debugging process was a nightmare. The infinite rendering was all happening in memory. No DOM nodes, no visual artifacts, nothing to grab onto. Just the browser slowly consuming RAM until it crashed. And it wasn’t an immediate crash, which made things worse: I’d load the page, poke around, everything looked normal… then 2–3 minutes later, the tab would blow up.

Chrome’s debugger would occasionally pause automatically with “Paused before potential out-of-memory crash.” Every time, it stopped in the same place: deep inside Motion’s code where it creates projection nodes.

That sent me down a rabbit hole for days. The stack traces were 10,000 parents deep and completely anonymous. Motion looked guilty. I became convinced that something about how we were rendering components was causing it to generate an invalid projection tree and then repeatedly attach to it, maybe because it was trying to attach to an unmounted DOM node, maybe because we were keying components based on editing state.

I even managed to prevent the crash by patching Motion locally and adding guards to stop the runaway projection node creation. But it was becoming obvious the projection nodes were a symptom, not the cause.

The real clue came from combing through the massive Motion ancestry path at the point the browser was about to run out of memory. Buried in the chain were a few layoutId values I recognized from the footer editor component tree. That gave me my first real lead.

On a hunch, I tried removing the <Activity> wrapper from the page footer editor popover. The app immediately crashed on load. Without Activity’s low-priority hidden rendering, the infinite recursion revealed itself instantly.

From there, I knew that the actual source of the issue was the footer’s editing UI. Trivial at that point to trace back through the history of commits touching the footer editor file and find where the readOnly prop had been removed.

Lessons and Learnings

Comments are documentation. Tests are constraints. This bug happened because I treated a structural invariant like a note instead of a requirement. In an AI-augmented codebase, that’s not a safe bet. Anything that can break the app deserves a test, not a comment.

Comments also don’t survive large refactors, especially when both humans and AI agents are touching the same files. I wrote that comment about infinite recursion, saw it as important enough to document, but didn’t take the next step of writing a test—even though it only takes about 20 lines:

// mock PageFooter to capture its props

const mockPageFooter = vi.hoisted(() => vi.fn(() => null));

vi.mock('~/components/PageFooter.tsx', () => ({

default: mockPageFooter,

}));

const mockProps = {...};

const expectedCount = FOOTER_VARIANT_CLASS_NAME_SCHEMA.options.length;

afterEach(() => {

cleanup();

mockPageFooter.mockClear();

});

describe('VariantPickerFooter', () => {

it('renders PageFooter components with readOnly: true on design tab', () => {

render(<VariantPickerFooter {...mockProps} />);

// verify mock calls match the expected count and all have readOnly: true

expect(mockPageFooter).toHaveBeenCalledTimes(expectedCount);

mockPageFooter.mock.calls.forEach((call) => {

const [props] = call as unknown as [ComponentProps<typeof PageFooter>];

expect(props.readOnly).toBe(true);

});

});

});

That’s all it would have taken. A tiny test asserting that every previewed footer is rendered with readOnly: true would have failed the moment the prop disappeared. Instead, the comment got deleted, the prop vanished weeks later, and the app quietly carried a timebomb that only went off after React had spent minutes rendering an infinite tree in the background.

None of this was malice, and it was far too subtle to expect anyone to catch it in review. It seems self-evident that we must up our code review game as more and more of our code is written by LLMs, but don’t fool yourself into thinking that’s enough. The failure wasn’t the agents or the reviewers; it was the lack of a constraint enforcing what the comment implied.

The real shift here is recognizing that AI changes the semantics of “good enough.” If something matters—if it’s a structural invariant, a recursion boundary, a hidden assumption—documenting it isn’t sufficient anymore. You have to encode it. A comment explains intent; a test preserves it.